[ad_1]

Economic sanctions, whether in the form of threats or actual implementation, aim to achieve political goals. For example, Western countries imposed a series of economic sanctions on the Russian economy due to tensions in the Crimean peninsula in 2014 or because of the special military operation with Ukraine in 2022.

The 2018 US-China trade war also brought problems with trade restrictions on the world’s two largest economies. At that time, the restructuring of supply chains in neighboring countries helped companies, politicians and investors to better recognize the risks posed by “sanctions”.

In this article, the authors aim to propose and provide a multi-dimensional, multi-objective perspective of economic sanctions. The above contents and approaches need to be explained in detail, from the mechanism to the connection relationship.

INCREASE PENALTIES MULTI-TARGET, LONG RANGE

When economic sanctions are imposed on a specific country (target country), most of the negative effects are usually transmitted directly to that economy.

However, recent research by Bayramov et al (2020), which points to an issue related to the imposition of sanctions by the West and the US on the Russian economy in 2014, has raised the issue in Vietnam. Trade transactions, remittances and foreign direct investment have declined not only in Russia but also in countries with historical roots with Russia (Central and Eastern Europe: Armenia, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Belarus, Kyrgyzstan and Ukraine). this sanctions policy. This implies the transmission of negative shocks to neighboring countries with a high degree of economic integration into the sanctioned economy.

In addition, the economic sanctions imposed on North Korea, Russia, Venezuela and Iran are a testament to the diversity of goals of the sanctioning party. In the case of Iran sanctions, for example, since July 2006 the US and EU have viewed the sanctions as a means for Iran to negotiate its nuclear program, a tactic to slow its development and force the Iranian government to change its human rights policy . A range of sanctions related to trade, finance, travel bans involving individuals and organizations, etc. have been imposed.

From a more microscopic perspective, how will companies in sanctioned countries respond to these harsh measures? From the business dataset of Cuba and Myanmar before a series of US sanctions, Crozet et al. (2021) that domestic firms from these two economies tend to shift exports to neighboring countries. Accordingly, countries bordering sanctioned economies are more likely to gain access to trade flows by “evading” sanctions. However, companies from US allies tend to avoid sanctioned economies (e.g. French companies are reluctant to do business with Iran but choose countries close to Iran to do business). Part of the explanation for this phenomenon is that ‘sanctions’ indirectly increase the cost of entering the market. As a result, sanctioned countries will lose while neighboring economies will benefit.

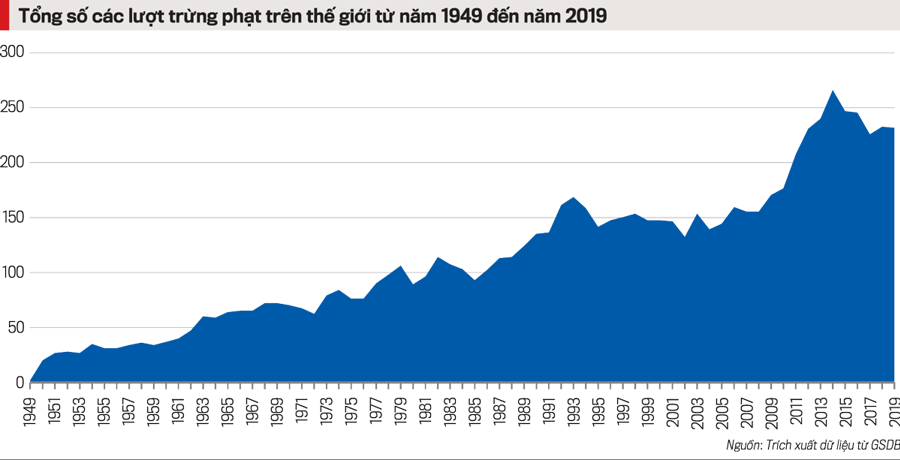

The trend for countries to apply sanctions is increasing. Using the Global Sanctions Data Base (GSDB) for the period 1949-2019, it shows that the number of sanctions has increased each year, particularly in cases of new sanctions occurring primarily in the 1970s and 1990s and thereafter started to skyrocket in recent years, along with the increase in diversity. In addition, there is also a regional asymmetry, as shown by looking at the sanctions of 1950, 1980 and 2019 between the sanctioning party and the sanctioned party. The complexity of sanctions has changed significantly in recent years, in terms of number, object, scope and type of application.

This group of authors also pointed out that the threats from the US are heavier than those from the EU, but the EU’s actions are more successful in practice. It should be noted that the economic impact can be different and heterogeneous for each member state, for example EU sanctions against Iran lead to differences in the unilateral relationship between member states and Iran depending on bilateral trade opening (Felbermayr et al., 2021). Trade sanctions from the early years were the dominant instrument, however other forms of sanctions such as financial sanctions, travel restrictions, arms embargoes etc., gas, military intervention and other forms of sanctions have emerged in the last 20 years.

UNDERSTAND NATURE, READY TO REACT

The debates surrounding the question: are economic sanctions effective? More specifically, can the punishing party achieve its political goals? What form of punishment is most effective? What is the economic cost to the sanctioning party and the sanctioned party? What are the implications for third parties and the rest of the world? Countries need to understand the deeper nature of economic sanctions in order to design countermeasures. It seems that economists focus solely on the impact of sanctions policies on the health of economies and financial systems, often without mentioning political goals, in order to clarify the main motives that the executing party makes the decision to punish with a desire to change the geopolitical landscape to change. Meanwhile, politicians have largely focused on determining the political implications of sanctions. At the same time, identifying factors that prompt a country or coalition to use economic policy as a sanctions tool.

For example, based on international trade theory, economists study the relationship between trade sanctions and trade levels (Dixit & Norman, 1980; Helpman, 1984) or use the theory, games, and economic behavior (Von Neumann & Morgenstern, 2007) to study conflicts between nations .

Politicians tend to draw on theories of international escalation and conflict (Carlson, 1995) and military conflict (Morgan & Schwebach, 1997) to explain the factors leading to sanctions and their effectiveness, implying that the executive party achieves its political goals. Figure 4 shows that the success rate of sanctions depends on the political goals that the country or coalition is striving for. With the exception of targets related to terrorism and democracy, sanctions have a 35% to 50% success rate when applied to the remaining targets.

Using the case of Russia, Huynh et al (2022) show that the Russian economy appears to be prepared for sanctions. As a result, oil and gas companies, owned by Russia’s billionaires, have created a protective shield against US and Western sanctions. They have prepared very well, stockpiling oil and gas (before the oil price surge), reducing spread investing and buying back shares in the market to avoid dilution ahead of these sanctions shocks. US and Western economic sanctions against Russia therefore appear to be ineffective.

Besedeš et al (2021) show that a total of 23 countries imposed retaliatory sanctions on German companies between 1992 and 2014. To prepare for, respond to, and adapt to these challenges, German companies doing business with these 23 countries have suffered temporary business risk losses.

Justifications for sanctions are often derived from negotiation theory (Smith, 1995) to signal the party threatened with sanctions to make concessions or suffer economic losses as a result of the measures. The negotiation theory arguments used to justify punitive measures against another country are actually just excuses, since sanctions rarely have a tangible effect. However, based on the argument above, why are sanctions still being enforced, even with increasing intensity and speed?

DESIGNING ACCESS TO VIETNAM

Vietnam is in a very “sensitive” position in international relations due to the problems of strategic competition between the US and China, as well as its traditional relations with Russia, Ukraine, East Asian countries and the United States, Europe and ASEAN countries persist. If relations in the unit have problems and show confrontations, this will leave Vietnam’s foreign and economic policy in a dilemma that requires a narrow approach: maintaining a balanced position, ensuring the principles of independence and autonomy in strategy, flexibility and flexibility in strategy for dealing with parties.

Currently, we need a new approach to explaining the link between economic and political sanctions, a link that is intentional and interdisciplinary, cross-goal relationships. This is also a stimulating way to frame Vietnam’s approaches in the new context.

The content of the article was published in the special issue Xuan Quy Mao of Vietnam Economic Magazine, published on January 23, 2023. Welcome readers to read This:

https://postenp.phaha.vn/chi-tiet-toa-soan/tap-chi-king-te-viet-nam

[ad_2]

Source link